Logical & Practical Fingerings for Scales in Double Thirds and Sixths

(Abstract) No scale system would be complete without scales in double thirds and sixths. Largely neglected by students and teachers from America and other western nations, double-note scales have for at least two centuries been the cornerstone of the “Russian Piano School”. Practicing scales in double notes is difficult but highly rewarding, in that the required techniques involved imbue students with incredible control, power, flexibility, and finger independence. Determining the most logical and practical fingerings for double-note scales is difficult and elusive. This article explains and justifies the fingerings used in Volume 3 (the double-note volume) of BachScholar’s Complete Guide to Major & Minor Scales.

Get Volume 3 (Advanced, Concert Level, Grades 8-11) of Complete Guide to Major & Minor Scales — PDF | Hardcopy

Get Volume 2 (Upper Intermediate to Advanced, Grades 5-7) of Complete Guide to Major & Minor Scales — PDF | Hardcopy

Get Volume 1 (Beginning to Intermediate, Grades 1-4) of Complete Guide to Major & Minor Scales — PDF | Hardcopy

(25% Off) Get Volumes 1-3 (complete bundle) of Complete Guide to Major & Minor Scales at a big discount — PDF

Symmetrical or Mirror Relationships in Double-Note Scales

No scale system on scales would be complete without scales in double thirds and sixths. This is an often neglected technique among American students, although it has been the cornerstone of the “Russian Piano School” for nearly two centuries. One reason why Russian pianists are known for their solid technical abilities is that Russian students routinely practice double-note scales from a young age, which if done correctly, imbues pianists with incredible control, power, flexibility, and finger independence. This is simply not so in America and some other western nations. The practice of double notes has unfortunately all but disappeared in the American system. Most American piano teachers and students either do not know about or have never bothered learning about the highly-coveted double-note scales. Hopefully, Volume 3 in BachScholar’s series Complete Guide to Major & Minor Scales will correct this situation and introduce more teachers and students to the great value of practicing scales in double notes.

Choosing the most logical and practical fingerings for double-note scales is difficult and elusive and seldom do experienced pedagogues ever agree 100%. Two of the most notable pedagogues who supplied fingerings for scales in double thirds and sixths are Louis Plaidy (1810-1874) in Technical Studies for the Piano (1852) and Isador Philipp (1863-1958) in Complete School of Technic for the Pianoforte (1908). Plaidy and Philippe both supply similar fingerings for scales in double thirds and sixths, many of which are awkward and strange. Apparently, neither of these influential pedagogues was aware of inherent symmetrical or mirror relationships shared by certain major scales, otherwise their suggested fingerings would have been much different. There are probably a dozen ways one could finger double-note scales; however, the most practical and logical fingerings can be devised only if the symmetrical relationships are allowed to take precedence.

The most important determinant in making logical fingering choices in double-third scales is recognizing symmetrical, mirror relationships between certain scales. The piano keyboard consists of two “mirror points,” D and A-flat, so that when progressing outwards from these two points the relationships of white and black keys are symmetrical or mirrored. Each major scale has its own unique mirror-counterpart, which happens to work out in a fascinating way.

The key signature of each mirror-counterpart is the same number of the opposite type of accidental (sharps instead of flats or flats instead of sharps) going in the opposite direction. For example, D major (2 sharps) ascending in the RH mirrors B-flat major (2 flats) descending in the LH. Likewise, B-flat major ascending in the RH mirrors D major descending in the LH. These observations suggest the axiom that whatever fingering is chosen for D major ascending in the RH should also be the fingering for B-flat major descending in the LH, and vice versa.

The double-third and double-sixth scale fingerings in the present system (in Volume 3) have all been derived using this law of mirror relationships. Most of the scales in double thirds require different fingerings, although it comes as a surprise that corresponding scales in double sixths work best with one fingering for all, a fingering which is the same symmetrically. Below is a summary of how these mirror patterns relate to one another.

Symmetrical or Mirror Relationships in Major Scales in Double Thirds and Sixths

C major ascending in the RH mirrors C major descending in the LH. This indicates the same fingering. In addition, C major has mirror fingering when played in contrary motion. (See Ex. 1)

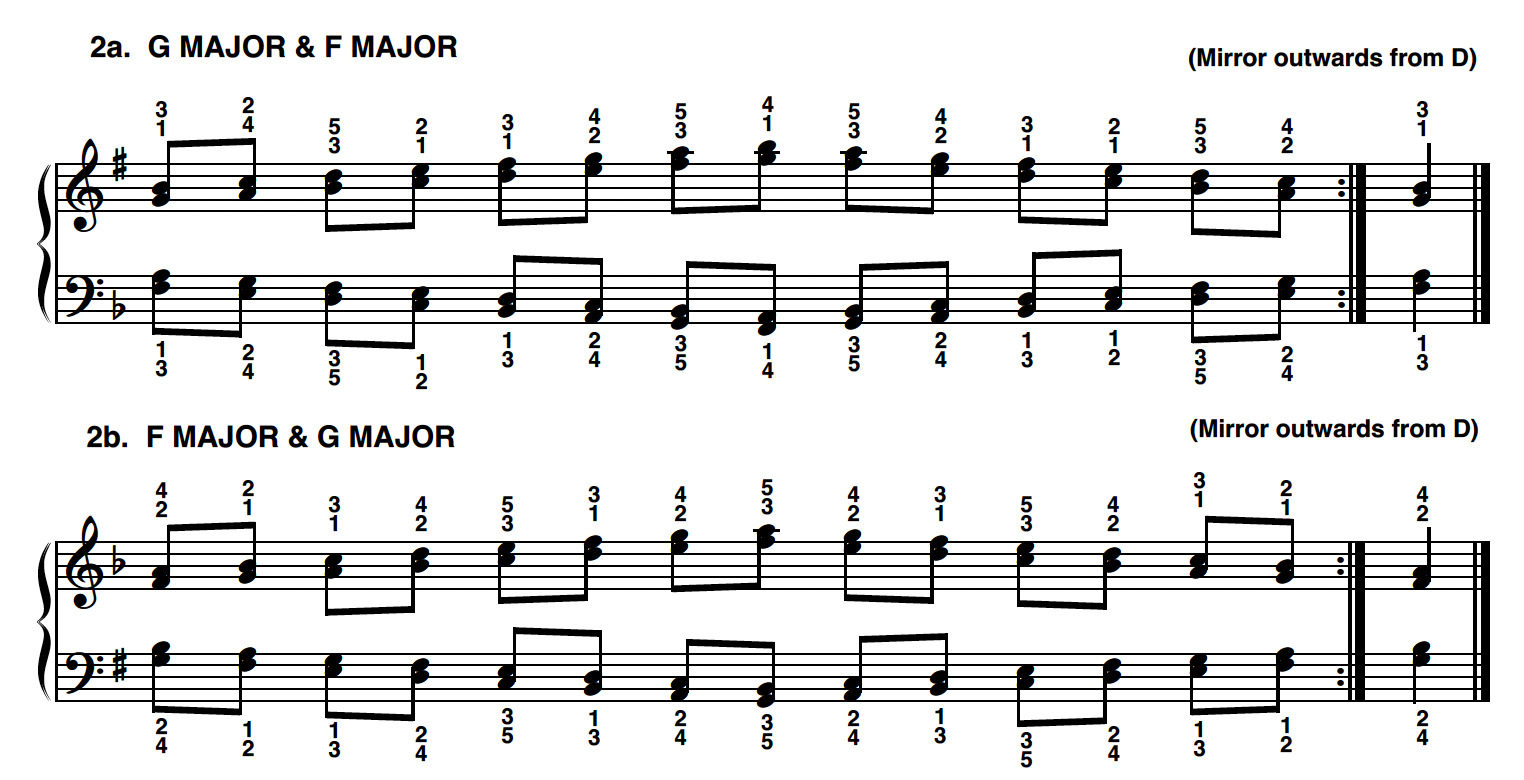

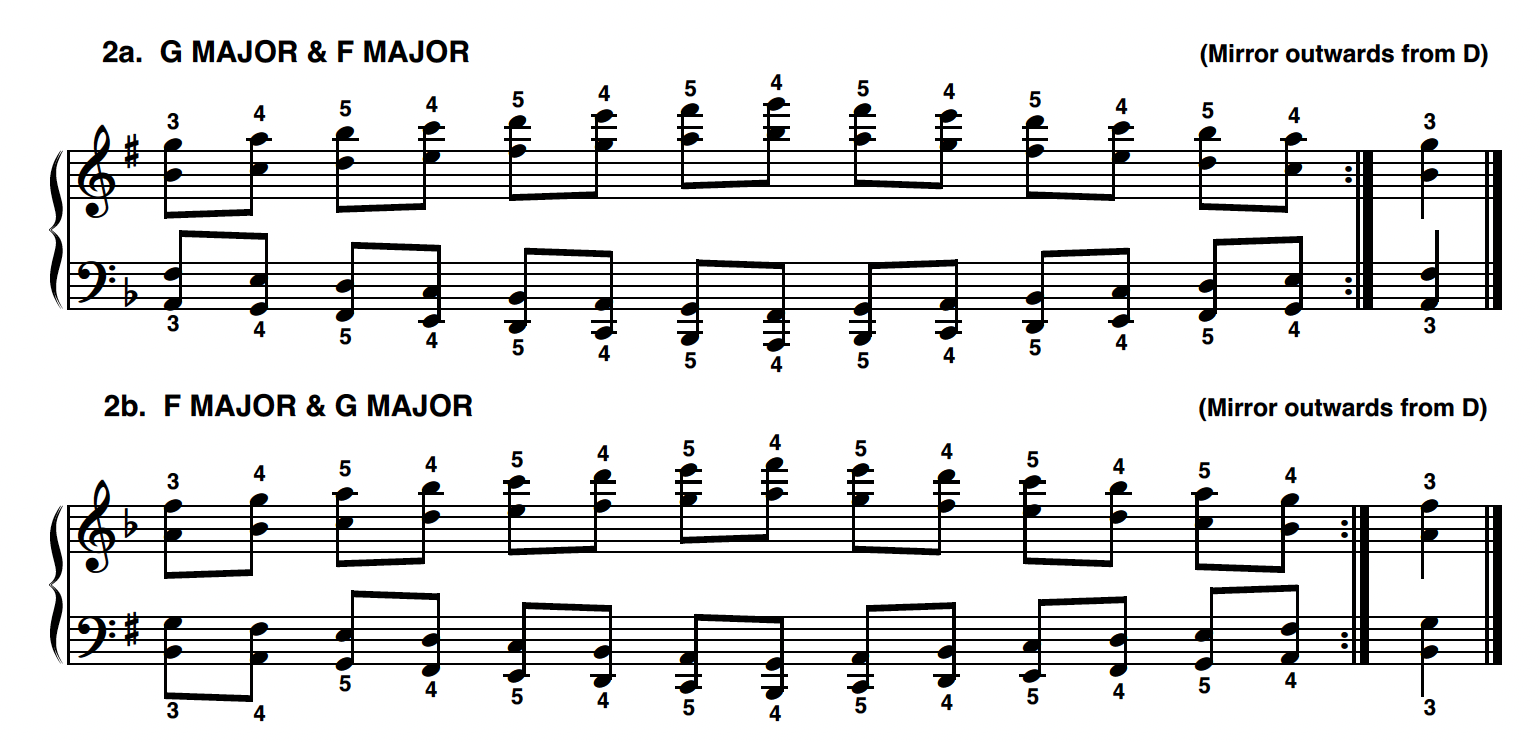

G major ascending in the RH mirrors F major descending in the LH. Conversely, G major ascending in the RH has the same fingering as F major descending in the LH, and vice versa. This indicates the same fingering for both pairs. (See Exs. 2a-b.)

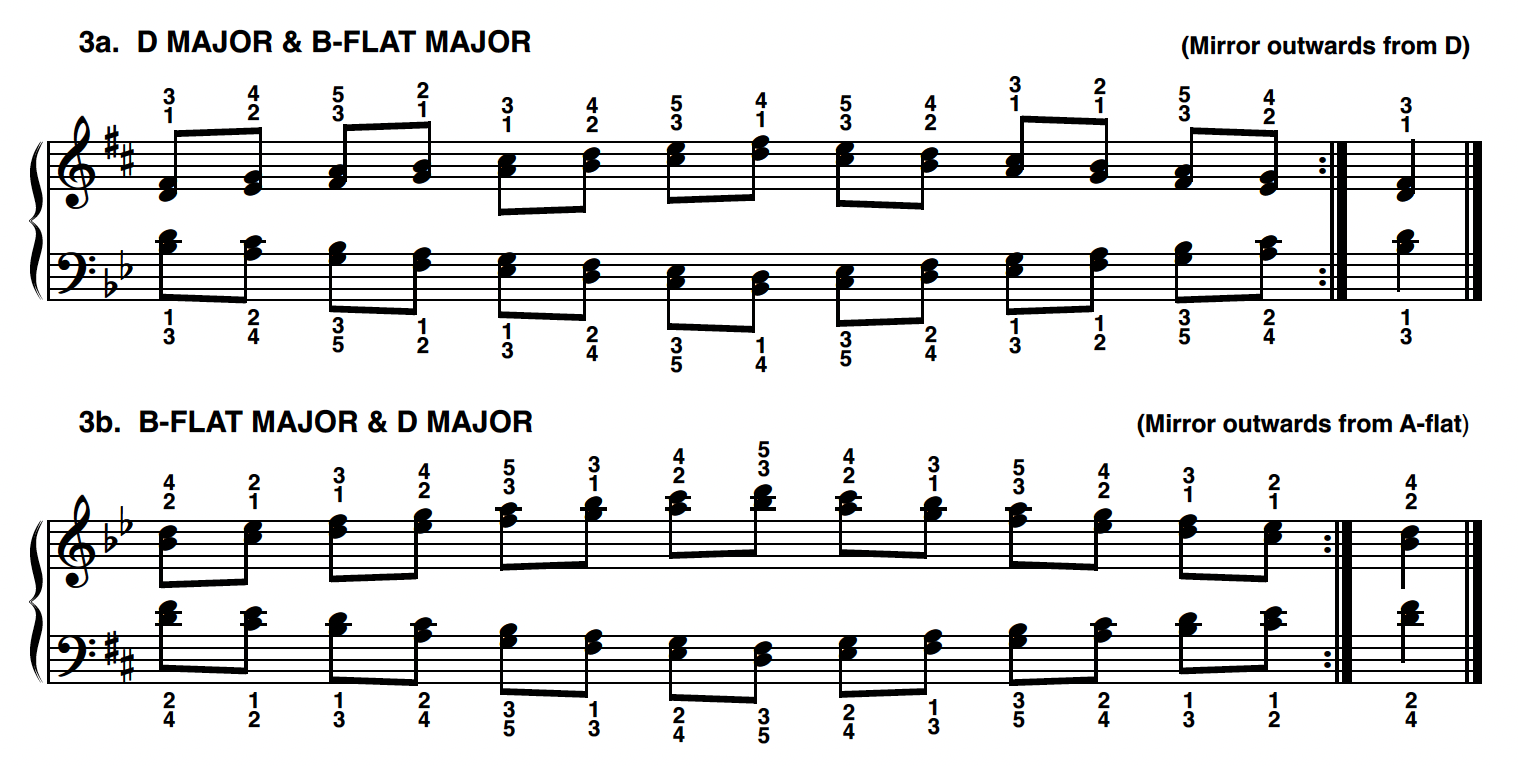

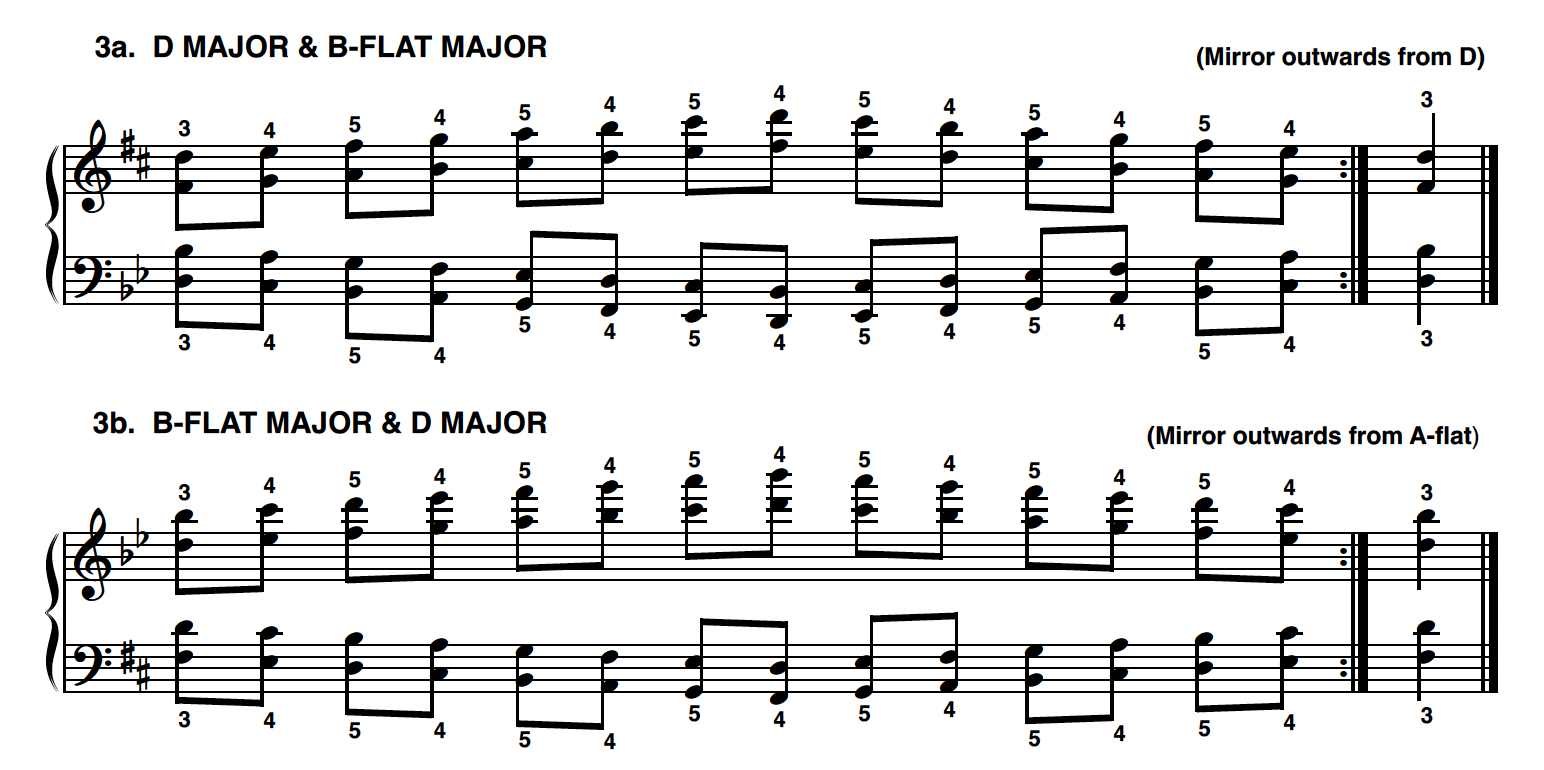

D major ascending in the RH mirrors B-flat major descending in the LH. Conversely, D major ascending in the RH has the same fingering as B-flat major descending in the LH, and vice versa. This indicates the same fingering for both pairs. (See Exs. 3a-b.)

A major ascending in the RH mirrors E-flat major descending in the LH. Conversely, A major ascending in the RH has the same fingering as E-flat major descending in the LH, and vice versa. This indicates the same fingering for both pairs. (See Exs. 4a-b.)

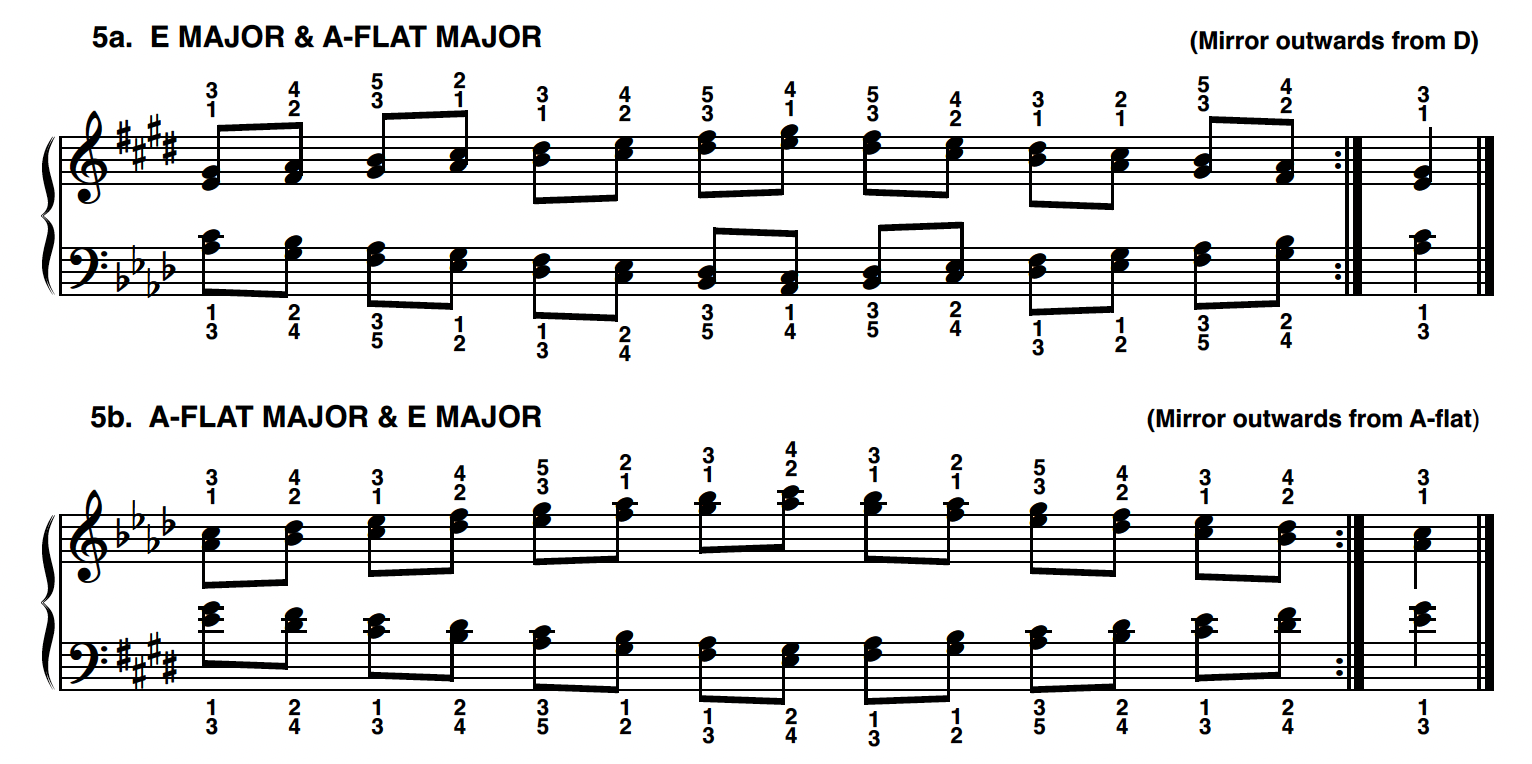

E major ascending in the RH mirrors A-flat major descending in the LH. Conversely, E major ascending in the RH has the same fingering as A-flat major descending in the LH, and vice versa. This indicates the same fingering for both pairs. (See Exs. 5a-b.)

B major ascending in the RH mirrors D-flat major descending in the LH. Conversely, B major ascending in the RH has the same fingering as D-flat major descending in the LH, and vice versa. This indicates the same fingering for both pairs. (See Exs. 6a-b.)

F-sharp major ascending in the RH mirrors G-flat major descending in the LH. Conversely, F-sharp or G-flat major have mirror fingering when played in contrary motion. This indicates the same fingering for both pairs. (See Exs. 7a-b.)

Introduction to Double-Third Scales

Scales in double thirds and sixths have been taught since the advent of the modern fingering system, which evolved to its current form around the beginning of the 19th-century. Double-note scales were highly esteemed by the 19th-century virtuoso school, which arguably is one of the most difficult techniques to learn and master.

The present system takes a different approach to fingering. Developed over a thirty-year period, this system is founded upon symmetrical or mirror relationships that help determine the most logical fingering choices for each scale. Moreover, this system includes the melodic minor, whereas Plaidy and Philippe include only the harmonic minor. The present system of fingering is explained on the WRP website (The Well-Rounded Pianist Piano Method — Introduction to Major & Minor Scales), which may be briefly summarized below. Below are listed some of the important rules or observations for double-third scales according to the present system of fingering.

General Fingering Rules for Double-Third Scales

Only the following finger combinations are used: 1-2, 1-3, 2-4, 3-5 in the RH and 2-1, 3-1, 4-2, 5-3 in the LH. 1-4 or 4-1 are used only as convenience fingers at the highest and lowest points (usually to make it easier than 1-3, 3-1).

All scales have one 3-4-5 (5-4-3) group and one 2-3-4-5 (5-4-3-2) group for each octave, except for convenience fingers played at the highest and lowest points.

C major and G-flat major in contrary motion are the only scales that have perfect mirror keys, and thus, mirror fingering.

C, G, D, A major have the same fingering in both hands.

E and B major in the RH have the same fingering as C major in the RH, but different fingerings in the LH.

All harmonic and melodic scales have the same fingering in both hands as the parallel major, except G-flat major - F-sharp minor and D-flat major - C-sharp minor.

F-sharp, C-sharp, and G-sharp minor (harmonic and melodic) have the same fingering in the RH.

C-sharp and G-sharp minor (harmonic and melodic) have the same fingering in the LH.

Introduction to Double-Sixth Scales

Scales in double sixths are much different than in double thirds, which naturally requires a different fingering system. While it is certainly possible to use a 1-3 and 1-2 finger combination in each octave for double sixths as done with double thirds, the present system instead uses one 3-4-5 combination and two 4-5 combinations for each octave, not including any “convenience” fingers played either at the beginning or end. Plaidy and Philippe also use one 3-4-5 and two 4-5 groups per octave, however, the present system often uses these two combinations in different places.

Like in the double-third scales, the fingerings for double-sixth scales are also governed by logical mirror patterns, for example, E-flat major ascending in the RH should have the same fingering as A major descending in the LH, as discussed in the previous section. Several possibilities exist for fingering double-sixth scales, however, the most important factor that simplifies the decision-making process is the observation of mirror patterns between certain major scale pairs.

This author has considered and experimented with several possibilities for each scale over the course of many years, but surprisingly, a profoundly simple possibility was eventually discovered that revolutionizes double-sixth fingerings. This possibility is the surprising observation that the same fingering works well for all 24 major and minor scales. Moreover, this fingering results in mirror fingering when played in contrary motion, which is simply not the case with almost all the double-third scales when played in contrary motion. Since one fingering applies to all scales, except for any convenience fingers played either at the beginning or end, this makes it much less difficult to memorize fingerings.

Below are listed some of the important rules or observations for double-sixth scales according to the present system of fingering.

General Fingering Rules for Double-Sixth Scales

Unlike double-third scales which require different fingerings for different keys, double-sixth scales work well with one fingering for all scales, major and minor.

Only the following finger combinations are used: 1-3, 1-4, 2-5 in the RH and 3-1, 4-1, 5-2 in the LH. 1-4 or 4-1 are used only as convenience fingers at the highest and lowest points (usually to make it easier than 1-3, 3-1).

All scales have one 3-4-5 (5-4-3) group and two 4-5 (5-4) groups for each octave, except for convenience fingers played at the highest and lowest points.

Played hands together in parallel motion, all scales alternate between one 5-4-3 (3-4-5) group and two 5-4 (4-5) groups which all occur at the same time.

Played hands together in contrary motion all scales (major and minor) have symmetrical or mirror fingering.