Minimalist Piano Fingering

DEAR READERS: Thank you in advance for reading this article. This is not in its final form, and probably will never be, since it is an ongoing article that I intend will grow into a full-size book in the very near future. I hope you return for more material soon. Also, do not assume this is your typical high-brow article written only for advanced pianists playing Chopin Etudes and Ballades. To the contrary, this article and the ideas within are primarily geared towards beginners and teachers who teach beginning-level students.

“Minimalist Piano Fingering” is a concept I coined in 2024. There is no better term for this type of piano fingering than this. I have been incorporating various minimalist techniques into my piano practice and performance over the last decade and I guarantee that it will revolutionize your piano practice and performance and open your eyes up to a whole world you probably never knew existed — piano fingering based on logic rather than tradition. One’s goal in fingering piano music, whether “real music” or exercises, is to find the easiest and not the most difficult solutions. The old school teaches that you must use certain fingers to “strengthen” them (which usually requires the most difficult fingerings), but if this technical goal takes precedence over the sound of the music produced and the effort required, it is a waste of time. Practicing and performing piano music should never be one of “strengthening fingers” but one of “making music”. Who cares if the fingerings given for scale passages in an edition of Mozart Sonatas “strengthen” the fourth and fifth fingers? To the contrary, one should always be searching for the easiest and most logical fingering, which is usually different from the traditional fingering. Minimalist piano fingering is all about discovering various tricks and hacks that make the playing of passages easier and the sound produced more clear and solid. This is ideal for open-minded students and teachers who have the courage to challenge tradition and carve out a new paradigm of piano fingering.

If you are interested in improving your piano fingering skills, BachScholar’s exciting new Focus on Fingering™ series is a must read and must own! Get one or more volumes in this series here (links below), where you may learn new and improved fingerings for the 24 major and minor scales, and study important piano works edited with new and practical fingerings based on minimalist principles:

Focus on Fingering™ — Fingering so easy it should be illegal!

🎉 CLEMENTI: Six Sonatinas, Op. 36, edited with new and practical fingerings — Order Hardcopy | Download PDF

🎉 A New & Improved System of Scale Fingering (includes the 24 major and minor scales) — Order Hardcopy | Download PDF

🎉 The 12 Major Scales with New & Improved Fingering — Order Hardcopy | Download PDF

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Emancipation from the Traditional C-Major Fingering Model

Minimalist piano fingering is the greatest undiscovered “fingering hack” in existence. But the first way of discovering clever shortcuts or “hacks” is by always trying out several possibilities. Too many pianists get stuck with one fingering and never venture out and explore new possibilities. Ideally, the inquisitive pianist should compare and rotate fingerings for the same passage. This teaches the valuable skill of adaptation which is needed in sight-reading and the playing of real music. My new fingering system goes by this motto:

The best fingering is often the one you haven’t tried out yet.

Before getting into details, it is first necessary to dispel a myth believed and followed by pianists for around two centuries. The myth is that the traditional C-major fingering (54321321 in LH and 12312345 in RH) must reign supreme all the time, that is, the assumption or belief that the C-major fingering must be used whenever full or partial scale passages occur in the major keys of C, G, D, A, E. Do you see already how ridiculous this kind of thinking is? But this is the way 99% of students are taught even today in 2024.

Just who made up such a rule and why do students and teachers religiously follow this rule when there are many possible fingerings for all these scales, most of which are as good or better than the traditional C-major fingering? For example, let’s get down to the very elementary level and play the C major scale just one octave up and back with the RH. Of course, all beginners learn the “correct” fingering here as 123* 12345*4321*321. This is so ingrained into our psyches that no student or teacher ever questions this fingering (except, of course…..mavericks and freethinkers like me, and you!). This fingering is also assumed to be the “correct” fingering for major and minor scales in C, G, D, A, E. Whoever invented this system obviously did not test out other fingerings to see if there are some that work as well or better. Spoiler alert……virtually all other possible fingerings work as well or better than the traditional fingering when playing all white keys. Therefore,

who is to say 123*12345 is the "correct” fingering in the RH for the C major scale? This would be like claiming white people are the best people in the world or that Southern Hemisphere people are smarter than Northern Hemisphere people.

Below are eight possible fingerings for the C major scale played with the RH using no fifth finger. There are of course more possibilities; however, the most common and logical options are listed here. Since 95% of all beginning music and exercises in most methods are based around the C major scale (which is fine, as I recommend the “C Major Method”), it would be advantageous for beginners to practice and learn all eight of these fingerings. They work extremely well and require the thumb to pass under 2, 3, or 4 with the same effort. Practicing the C major scale with as many as eight different fingerings (RH only for beginners) trains all possible finger and thumb crossings while the old boring 123*12345 does not. As early as possible in their training, beginners should learn to adapt to slightly different finger combinations using only four fingers, 1234. The best way to do this is to practice the C major scale with various fingerings. This is what virtually all beginner methods lack, to their great detriment.

Imagine learning piano for five years (at any age) and your teacher has led you into believing there is just one correct fingering for the C major scale. This would be like believing there is only one master race of people, which happens to be white people. There are many people in this world, all with different skin colors, and all deserve as much respect as white people. Young children are taught this at home and in school (at least with responsible parents and teachers). Then, why the snobbish and non-inclusive attitude that "there is one correct fingering” for the C major scale? Imagine if you worked hard on piano and fingerings for a full five years to find out your teacher never pointed out that the C major scale can be played very easily with as many as eight different finger combinations? Wouldn’t you want to fire your teacher?

Practicing the C major scale with as many as eight different fingerings should be the foundation of the beginner’s piano training, which is the best way to prepare beginners for more sophisticated passages in real music later on.

The traditional C-major fingering method as well as practicing Hanon only with 12345 or 54321 barely trains the thumbs and places unnecessary emphasis on the fifth finger, which is the smallest, weakest, and most useless of all five fingers. This causes bad hand positions, stress, and tension especially in beginners. On the other hand, the thumb is the strongest and most mobile of all five fingers, and to simply relegate it to the first position (C) and nowhere else is irresponsible and not realistic. (This is why Hanon exercises are better practiced with no fifth finger and with more thumb crossings.)

If one were to devise a perfect beginner method, it would have to be one that trains the thumb to pass under 1, 2, 3, or 4 with ease and fluidity and one that uses the thumb more frequently than 5. This mostly applies only to RH scales and scale-like passages and not the LH where 5 is used effectively for low bass notes. Pianists steeped in the traditional system usually have problems doing this because they have not learned how to use the thumb efficiently (because of only playing 123*12345 for scales and 12345 and 54321 for Hanon). Training the fifth finger will come through time; however, expecting beginners to master this finger is like expecting a beginning gymnast to do handstands. Beginners should not be expected to play fast scale passages with 5, and in the perfect beginner method 5 should be left out most of the time. Don’t worry though, the pinky does not have “feelings” and so you will not be offending it by not using it. The traditional system has this crazy unwritten rule that all five fingers must be used all the time to “train all five fingers equally” as if a finger may be offended for not using it as often as the others. Expecting to train the fifth finger to be as strong, fast, and responsive as the second or third fingers is like expecting a marathon runner to compete with sumo wrestler in a strongman contest. It simply will never happen. This is why it is always easier to simply change to an easier fingering rather than struggle with achieving equality between the weakest fingers (4 and 5) by hours and hours of torturous practice.

Now, your assignment is to try out all eight of these fingerings at slow, moderate, and fast speeds and compare/contrast the feelings in your fingers and hands as well as the sound created. Each fingering variation results in a slightly different feeling and sound. None of these are necessarily “better” than the other, but rather, each fingering has its own unique strengths and qualities. Personally, my favorite fingerings out of all eight are Nos. 5 and 7. I love the feeling of the B-flat and A-flat major scale fingerings played on all white keys. These fingerings are easier and more ergonomic for beginners than the traditional 123*12345, and what is more, they employ more thumb crossings which is a good thing since this trains the thumb in various ways the traditional fingering does not.

All beginners and intermediates who need remedial training should practice these eight fingerings daily one and two octaves. The goal should be to play the eight fingerings as fast as possible while keeping the most even tone among all notes. Duplicating or mirroring the fingerings in the LH is recommended but not mandatory, since 90% of all fast scale activity occurs in the RH. For the LH, it is best to focus more on chords and arpeggios since this is what is found most of the time in real music. However, if a beginner or intermediate truly wants to get to the next level of piano technique, scales with these fingerings played hands together is required (LH fingerings are indicated below each staff).

Instructions for Practicing the Eight Fingerings:

Play each scale, RH alone up and back several times. Disregard the half note at the end until the final bar.

Start with a slow but steady tempo for each example, like quarter = 84 bpm. This is your slow, base tempo.

Work up to about two times faster, in this case, half = 84. This is your moderate tempo.

Finally, work up to two times faster, in this this case, whole = 84 (just pretend the quarter notes are sixteenth notes). This is your fast tempo.

Total beginners should focus only on the RH while intermediates and above should use both hands (played an octave apart).

Aim for at least three times up and back for one octave, then extend the same patterns for two octaves up and back.

These eight fingerings are guaranteed to produce faster and more even scales than could ever be possible using the traditional C major fingering. They are the foundation of the minimalist system.

In my recent publication, A New & Improved System of Scale Fingering, which spawned the whole idea of “minimalist piano fingering,” I compare and contrast the traditional and new fingerings. It is discovered that out of 24 major and minor scales in the traditional system, the C major fingering occurs a total of 10 times. It is clearly the “default” fingering for most keys as all piano teachers are aware. By contrast, the F major scale fingering only occurs two times, for F major and minor. In the new system, however, the C major fingering occurs only once (RH for B major ascending). Making up for this lack of “standard” or “default” fingering in the new system is the fact that the F major fingering occurs a total of seven times. Thus, if there should be any standard, default kind of scale fingering it should be F major and not C major. This is because the F major fingering in the RH, 1234*1234, does not need the fifth finger and is equally divided into 4 + 4 finger groups, thus making it an ideal fingering for an ascending C major scale like in the opening of Clementi’s Sonatina No. 3 (discussed a little later with musical example).

Most teachers and students overlook the fact that it is very easy and (I think) easier to play all the scales that traditionally use the C major fingering with the F major fingering.

“Academically correct” fingerings are always the worst possible fingerings

Have you ever wondered how many different valid ways there are to finger the subject in the first two bars of Bach’s Invention No. 4? There are probably at least a dozen ways, the eight most likely ways shown here with numbers. No. 1 is the so-called “academically correct” fingering in that it uses all five fingers and from this perspective seems to be the most logical and best fingering. This is the fingering I used as a child up to probably my thirties. But then I grew up and became much wiser and discovered that using only a total of four rather than five fingers was all that was needed here and that passages are always easier the fewer fingers they employ. Thus, I have crafted seven more possible fingerings (Nos. 2-8), all of which follow a logical “regression” of fingers. In general, the fingerings get easier as the numbers progress. At the moment of writing this article, my preferred fingerings are Nos. 6 and 8 and a close second with No. 5. I can hardly even play No. 1 anymore. It seems so difficult now after using more minimalist fingerings for around two decades.

It is very interesting that the worst fingering of all eight possibilities is the academically correct No. 1, which uses all five fingers and has only one thumb crossing. In contrast, the best fingerings are the ones that use the least fingers and have the most thumb crossings. This is the opposite of the traditional fingering philosophy, which teaches to use all five fingers and avoid thumb crossings as much as possible. Of course, it is clear to see that the traditional fingering system is illogical and difficult technically because it favors the weakest fingers and discourages use of the strongest fingers, namely the thumb. The thumb is the strongest and most versatile of all five fingers, so it would stand to reason that the best fingering system would be the one that employs the thumb the most. It makes no sense to use the thumb as infrequently as possible, and instead, try to use the fifth finger all the time, which is the weakest and most useless of all five fingers. The fifth finger is especially weak when played on a black key as in No. 1, which can easily be fixed by replacing 5 with 3 as in Nos. 2-4.

Crossing a longer finger over a shorter finger, such as 3 over 4, is a technique I use now frequently as a mature player. I would have never used this technique in my twenties, the only reason being I didn’t know about it. Actually, I think I remember most teachers discouraging putting 3 over 4 and disregarding it as a bad technique that shouldn’t be used. I vehemently disagree now in 2024. Crossing 3 over 4 like in Nos. 2-4 is a highly effective and useful fingering technique that should be practiced by all. I absolutely love the way No. 2 feels and it is one of the best and most novel of all eight fingering possibilities (along with No. 3). Now let’s move on to another example, the opening four bars of Clementi’s Sonatina No. 1, which primarily concerns the scale passage starting at the end of bar 2.

Have you ever wondered how many different valid fingerings there are for the famous opening four bars of the Clementi Sonatina? Sadly, too few pianists ever have, since our early education system stresses conformity to rules and it is usually the academically correct fingerings indicated in most editions that win out. So let us now explore. I have discovered a total of no fewer than six possible fingerings, which like Invention No. 4 are ordered from the most difficult, and hence academically correct at No. 1, while the simplest and most minimal is No. 8. Take extra note as to how the six fingerings regress from No. 1 to No. 8 in order of complexity, that is, each successive fingering gets a little less complex in the number of fingers they employ. I think I may have played No. 1 as a child, which is by far the most difficult of all possibilities. If I had to choose the best out of all six, it would have to be No. 5 followed closely by No. 6. No. 5 is the perfect fingering for this particular passage. Not only is it the easiest to play, but it teaches students a group of four notes in a row (a tetrachord) followed by a crossing, how to play 1-2 quickly back and forth, followed by how to play three notes in a row followed by a crossing. The academically correct fingering in No. 1 does none of this and is only torture especially for beginners. This is because the player is expected to play the weakest finger combination (3434543) at a fast tempo. This is like expecting a beginning gymnast to do handstands. Once again, the best option is No. 5, which is what I chose in my recent edition of Clementi Sonatinas, Op. 36, followed closely by Nos. 4 and 6.

The minimalist style fingerings like Nos. 7-8 for Invention No. 4 or Nos. 5-6 for Sonatina No. 1 use fewer fingers and the strongest fingers (1-2-3) are given full advantage. On the other hand, the academically correct fingerings downplay the strongest fingers and instead emphasize the weakest fingers, and especially, the awkward finger progression 3434543. Why make things harder than they have to be? To prove this point, one simply has to try out a few or all of the fingerings and compare. For example, play fingering No. 1 for Invention No. 4 a few times over, then immediately play fingerings No. 5, 6, 7, or 8. Then go back and repeat. Do the same with fingering No. 1 for Sonatina No. 1 compared to fingering No. 4-6. Make sure to play at exactly the same tempo for each example and concentrate on the sound produced with an emphasis on evenness and solidness of tone. Also, rate which is easier or harder and which one you could play with no errors up to tempo with no warm-up. The vast majority of pianists will choose the minimalist fingerings as being more solid and reliable as well as easier to play. After playing the traditional fingerings for an extended period of time, the minimalist fingerings often seem so easy that you feel guilty for “cheating”. After all, the scale passage in fingering No. 6 in Sonata No. 1 shows that three fingers can do easily what most attempt to do with five fingers. The three-finger approach in this example wins every time in that it produces the most consistent even and solid tone with the least effort. Trying to do anything with five fingers when it can be done easier with three fingers is foolish.

Minimalist fingering techniques often seem so easy they should be illegal, but who sets the rules or laws? It is shown in A New & Improved System of Scale Fingering (BachScholar, 2024) that the traditional C major fingering model — 123*12345 (RH) and 54321*321 (LH) — is not the most optimal fingering for the C, G, D, or A major scales. Each of these scales has a different fingering in the new and improved system. This being the case, there is hardly ever a reason to use the C major fingering (with 5) in scale passages. A simple solution to de-conditioning yourself to always play the traditional C major fingering is to play the F major fingering instead. The F major fingering in the RH omits the fifth finger and plays 4 instead of 5 on tops of phrases. Sticking to this general rule is the first step to going the minimalist route.

For example, especially in Classical Era composers if the editor suggests 5 at the top of of a phrase of fast sixteenth notes then usually playing 4 instead of 5 does the trick, but this usually also requires changing the fingers before and after. A good example of this is in the opening bars of Clementi’s Sonatina No. 3. Bar 2 features an ascending C major scale, which 99% of the pianists on the planet would finger as 123*12345. But simply changing to an F major fingering (the F major fingering is sort of like the “C major fingering” of the new and improved system) improves the ease of play as well as the sound produced. I have taught this passage a million times and every time without fail if the traditional fingering is used the student plays the F too loud since it is played by the thumb. But this F should not be accented. If any notes are accented it should be C and G. When I was a young and inexperienced teacher I used to simply recommend practicing the C major scale with the traditional fingering over and over again to “strengthen” 4 and 5 and to “not accent the thumb on F”.

But then when I became more experienced and wiser I began recommending the F major scale fingering, which immediately solves the problem of the unwanted accent F and groups the sixteenths neatly into 4 + 4 finger groups. In addition, the top notes are easier to articulate using 432 instead of 543. But then I became older and even more wise and went out on a limb and dared to try just three fingers. The feeling is amazing and difficult to describe. It was like a heroin addict’s first fix. If you have a good thumb technique, which is easy to develop as a beginner, fingering No. 3 should seem even easier and more reliable than fingering No. 2, which is a huge improvement over fingering No. 1. I especially like the clarity and precision you get on the top notes using 1-2. This is the fingering I suggest in my edition of Clementi’s Six Sonatinas, Op. 36. It is a superior fingering to No. 1 in every way but you will feel guilty because of being conditioned by the establishment into using the obligatory five fingers for scale passages. The three-finger technique does not always work, but it is highly effective especially in short and quick scale passages that change directions. The thumb is the best finger for maneuvering around these types of passages. Notice how the thumb is played two times more for the scale passage in fingering No. 3 than in fingering No. 1. This is a good thing.

The C major fingering model fails even more when applied to triplet-style rhythms. For example, the third movement of Clementi’s Sonatina No. 4 features fast, rolling triplet sixteenths in bar 46. There is no reason to use all five fingers here with the academically correct C major fingering. Instead, simply using 321 for each triplet group greatly enhances the clearness of tone and consistency of accents. It is a fingering that needs virtually no practice to play perfectly with no warm-up. This is because fingers 1-2-3 have powers greater than 3-4-5.

In the popular Op. 299 (40 studies divided into 4 books of 10, semi-progressive in order of difficulty), Carl Czerny (1791-1857) begins his opus with two studies, one mostly RH and one mostly LH, that teach the C major fingering both ascending and descending. Ironically, the C major fingering is the worst fingering you could possibly use here (No. 1 below). A much better fingering than the traditional is simply to take the first three sixteenths with 321 and the next three groups of four sixteenths with 4321 (No. 2 below). This fingering makes it much easier to put slight accents on the notes that should have accents, if any. Using the C major fingering here creates a less homogenous sound between fingers due to more overhead. Simply eliminating 5 and playing just four fingers improves everything. But why stop here? Trying out these passages with just three fingers, 1-2-3, results in a sound and clarity that four or five fingers cannot possibly match.

Below are bars 1-3 and 5-7 of Op. 299, No. 1 and bars 1-3 of Op. 299, No. 2 all with three different fingerings that regress from hard to easy. Pianists who use the traditional fingering here are living in the Dark Ages. It is obvious that fingerings No. 2 and 3 are both better than No. 1 in every way. The playing says it all. Try all three at the same tempo and rotate the three fingerings with little pause between. Do this several times, rest and repeat. Then, after a fair try on all three which one produces the least clean and even touch and which one produces the cleanest and most even touch? The answer to this is fairly obvious.

Even if one is opposed to this minimalist fingering philosophy and chooses to use the traditional fingering, all pianists and especially beginners can benefit from practicing minimalist style scales and exercises. Pianists who have been steeped in the traditional system for an extended period often lack thumb mobility since the traditional fingerings usually avoid the thumb as much as possible. Minimalist fingerings develop a fast and mobile thumb, which can be done with specific thumb exercises. The most basic of all such exercises is a two-octave C major scale played with three fingers, shown in No. 2 below. Playing a two-octave C major scale with just three fingers is one the most useful exercises for freeing up tightness in the thumb muscles. Ironically, it is the easiest fingering of all three in the examples below. All pianists, regardless of level, should practice three-finger scales. They result in the most even touch and dynamic control of all three fingerings. What is more, three-finger scales can be learned in much less time than the traditional fingering. For example, I taught a six-year-old beginner once and it took at least six months to play the C major scale two octaves with the traditional fingering at a moderate tempo. Amazingly, in just one week using just three fingers the scale was cleaner, faster, and more controlled than six months with the traditional fingering. The main reason the traditional fingering for C major is so difficult for beginners is that the thumbs do not play at the same time except for C half way through. Otherwise, the right and left thumbs cross under at different times. This is extremely confusing for beginners. (By the way, in A New & Improved System of Scale Fingering, the thumbs play together all the time!) Anything that is confusing for beginners should be viewed with skepticism.

Complementing three-finger scales are four-finger scales, shown in fingering No. 3 below. Pianists need to master three-finger and four-finger scales and be able to freely transition from groups of threes to groups of fours. After all, this is all major and minor scales are, that is, patterns of three-finger groups followed by four-finger groups. This holds true in the traditional system as well as in the new and improved system. Now, try out the three fingerings for a two-octave C major scale. Play one, then another, rotate, repeat. After some experimentation and adaptation to some unfamiliar fingerings, it is easy to see and hear that the three and four-finger fingerings are better in every way.

Applying this to real musical examples takes some rethinking if you are steeped in the traditional system. For example, consider the first movement of Mozart’s Sonata in C, K. 545, bars 5-10. Here are white-key scales going up and down, which most pianists finger with the traditional C major fingering (No. 1 below). This fingering can be vastly improved by simply removing the fifth finger and re-fingering each measure starting with 2 followed by a 123 group and four 1234 groups. In other words, each scale ascending is played with the B-flat major scale fingering (which is the same as the traditional in the new system) while each scale descending is played with the F major fingering (also the same as the traditional in the new system), which can be seen in No. 2 below. The entire six measures can be played more efficiently with no fifth finger.

The fifth finger is problematic when used for fast scale passages that maneuver or go up and down. Almost always, it can be replaced by the much more stable fourth finger and an alternate fingering other than the traditional can always be found. One of my favorite examples of this as well as the ridiculousness of the traditional C major fingering occurs in Czerny’s Op. 299, No. 9, bars 49-54. First off, a birds-eye view of these six measures shows all white keys with no black keys whatsoever. This means that fingering is an open slate. Czerny and all editors after him specify the C major fingering for all six sequences and this is how virtually all pianists finger it. That is, the top notes in each phrase are always played by 5 followed by one 54321 group and one 321 group. Look closely at the patterns and experiment with some fingerings other than this traditional model. You will discover that the entire six-measure passage can be fingered with four-finger groups ascending and three-finger groups descending. In other words, when playing this passage simply think 1234 + 1234 going up then 321 + 321 + 321 going down and repeat this cycle six times. Nothing could be easier. In contrast, adhering to the traditional C major fingering here can be a miserable experience especially for less advanced students who may not have total finger independence of all five fingers. This ingenious minimalist-style fingering makes this passage easily playable even by beginners. Omitting the fifth finger here is key. The fifth finger in this passage is totally useless and even a detriment. Adding to the minimalist nature of this fingering is the LH fingering, which can be done by simply repeating the third finger on each bass note, that is, descending 31 31 31. Some damper pedal may also be used here.

Now, as an experiment, play this passage using the traditional C major fingering, 123*12345, then try out this much improved fingering that groups fingers into threes or fours. The difference is night and day in the ease of play as well as the evenness of touch, not to mention memorization. If you have ever played or practiced this etude already, why did you not think of this fingering yourself? It is probably because you wanted to be “safe” and not venture out and try anything that goes against tradition. If this is the case, simply recite the following aphorism a few times and perhaps in similar passages in the future it will inspire you to dare to think outside the box. Remember that:

The best fingering is often the one you haven’t tried out yet.

The new suggested fingering for the white-key passage in Czerny’s Op. 299, No. 9 is simple in theory and also in practice, but only if one has mastered the playing of threes (123 or 321) and fours (1234 or 4321) separately. I believe one of the mistakes in modern piano pedagogy is teaching traditional scale fingerings before the student has even had a chance to master 321 or 4321 separately. Each of these requires a different placement of the thumb and finger crossovers, which suggests that they are best practiced separately. Then, after each skill is practiced and mastered, they may be assembled into groups of threes and fours which are full scales.

Since the two main finger combinations in scale playing are 123 (321) and 1234 (4321), it makes sense to isolate these two patterns and practice them separately a few of different ways. First, four series of 123s are played whose first and last notes are the same, causing three-note slurs among triplets (See 1a.) Next, four series of 123s are played ascending and descending in a scale that covers an octave and a fifth (See 1b.)

Next, three series of 1234s are played whose first and last notes are the same, causing four-note slurs (See 2a.) Next, three series of 1234s are played ascending and descending in a scale that covers an octave and a fifth (See 2b.)

Once one has a good handle on mid-tempo scales using 123 and 1234, like examples 1-2 above, the next step is to drill these patterns with smaller ranges but faster tempos. For example, Ex. 3a below shows fast tempo sprints using 123 and 321. The notation here looks more difficult than it really is. All you are doing here is playing 123 (321) two times in a row up and back (with repeat) followed by 123 (321) three times in a row up and back (with repeat). Ex. 3b. below does the same thing but in groups of four. This exercise is especially great for beginners, since it builds a strong 123 (321) base with the three strongest fingers. This particular notation makes it possible to practice these with metronome. Start with a moderate tempo like eighth note = 63 and progress upwards as fast as you can play while still retaining precision and control.

Occasionally, the pianist encounters several C major scales in succession like at the end of Burgmüller’s Op. 100, No. 25. In cases like this, it is always less hassle and easier overall to use the four-finger technique especially in very quick scales like this. One must stretch a tiny bit more for this fingering, but when mastered the clarity and precision is unmatched. Four-finger groups here make so much more sense than bothering with the fifth finger and being so concerned with employing all five fingers. After all, the notes are grouped into fours (i.e., sixteenth notes), therefore the most logical fingering is one in which the fingers are also grouped into fours. This is a more even distribution, which produces a more even touch.

The four-finger scale technique comes in handy, and basically, it can be used effectively for any white-key scale passages, especially sequences, like in Czerny’s Op. 299, No. 5. These are quick, one-octave scales like in the Burgmuller example above, which are best fingered in groups of four in both RH and LH. It makes no sense to play the traditional C major fingering here, as all pianists seem to do. By using the four-finger technique, correct accents are more easily produced than with the C major fingering since the thumbs play on every beat. Placing the thumb on the fourth sixteenth note in a four-note group, as the traditional fingering does, causes the scale to have a slight accent or bump where it doesn’t belong. This causes unevenness and eventually frustration. This is easily fixed by omitting the fifth finger.

Ever since I started incorporating the four-finger technique into my playing (about 15 years before writing this article), it has seemed almost blasphemous, if not darn near impossible, to go back to the traditional C major fingering. I also discovered this to be the case with the playing of five-note scales, also called pentascales. Have you ever wondered about how conditioned into conforming to rules most pianio students are? We are all taught from day one of piano lessons that when you have five notes in a row, like CDEFG, the “correct” fingering is always 12345. Then, we go through life playing the piano for many years and every time there are five notes in a row, even at age 45, we automatically play fingers 12345. But why not 21234 or 12343? These are perfectly doable and very comfortable ways to finger a five-note sequence on white keys and we have ignored these possibilities for all these years. Why do all the method books ignore these? To really become a master of minimalist fingerings and to decrease the frequency of always relying on the fifth finger, the most useless of all five fingers, there is nothing better than a simple pentascale exercise.

Below is a common type of exercise used in many method books, which is simply a succession of quick pentascales ascending and descending, all on white keys. If given no fingering, most pianists would automatically assume the only and best fingering to be 12345 or 54321; however, I argue that a much better and more practical fingering exists. Instead of playing the fifth finger on top in the RH, simply cross 3 over 4. This is a very quick movement, which needs to be accentuated with a sharp staccato. The third finger is the perfect finger for a solid staccato as well as a slight accent. It moves easily over the fourth finger with a little practice. Since the traditional fingering system disregards crossing 3 over 4, and many teachers discourage its use, pianists who are steeped in the traditional system never have the opportunity of practicing this fascinating and effective technique (which was purportedly used often in Baroque Era keyboard fingering). When the RH descends, however, this fingering cannot be reversed but rather 43212 works better. This requires a quick crossing of 2 over 1, which is very easy. The LH does the same but reversed, that is, it plays 43212 ascending and 12343 descending. This is a phenomenal exercise that all pianists should practice. These two fingerings for pentascales are better than using all five fingers because they produce a more solid and even touch and make accenting the first and last notes easier if you desire to do so. If you have never played fingerings like these before, please have patience. I guarantee that after you have this amazing fingering mastered you will never go back to 12345 again!

After becoming thoroughly accustomed to crossing 2 over 1 and 3 over 4 for pentascales and being able to play the above exercise fluently and effortlessly, you will never see familiar pieces like Burgmuller’s Arabeque (Op. 100, No. 2) the same ever again. Most pianists do not realize that a better fingering than the traditional exists for this very famous piece. Just like in the exercise above, crossing 3 over 4 for the RH ascending is more effective in producing a clear touch with a slight accent on the last note (played staccato). The small and weak fifth finger is unreliable for this, especially for beginners. Crossing 3 over 4 is a useful, valuable, and underused technique and the Arabesque is a perfect little piece for learning this technique. Anyone can play 12345 but not anyone can play 12343.

After the repeat, Burgmuller introduces the theme in the LH, in which there also exists a more logical and easier fingering. there is an easier fingering. Playing the first G-sharp in the LH with 4 (instead of 3) and the first E in the RH also with 4 makes this passage even easier due to “symmetrical fingering”, a concept discussed later in this article. Also, the LH fingering for the pentascale crosses 2 over 1. It’s not that the traditional fingering here is difficult by any means, it’s just that using more 4s in both hands seems more logical and they are more fun to play than the ho-hum-boring traditional fingering. Pianists should learn that five notes in a row does not mean one must use all five fingers.

Have you ever tried out all the various ways to play the C major pentascale using only three or four fingers? I can think of four main ways, shown below, Each should be repeated fast and evenly. Your goal is to practice each and compare the feelings and the sound produced with each fingering. The easiest to play and smoothest sounding are Nos. 3-4. But Nos. 1-2 are valuable to practice as well, since these develop lightening quick thumb mobility. Unfortunately, with an emphasis on fingers 345 and downplaying of the importance of the thumb in the traditional system, there is hardly any place to practice this useful technique. Make sure to start slow and work your way up the tempo ladder. This is an especially indispensable exercise for beginners since it is the most effective way to train the thumbs.

Most piano methods, perhaps all, teach pentascales in keys other than C with all five fingers. There seems to be an unwritten rule amongst old-fashioned piano pedagogues and conservative teachers that students must use the five fingers equally as if fingering should be a democratic process. Just because you have five fingers does not mean you need to use all of them all the time. The fifth finger in either hand is a useful finger for certain techniques but not a very useful finger for other techniques. Fast scale activity is one of the techniques the fifth finger is bad at. When playing fast, repetitive pentascales it is easier to attain an even touch and fast tempo when the fifth finger is omitted. This always requires more thumb and finger crossovers than if all five fingers are used, which goes against the traditional fingering philosophy of avoiding thumb and finger crossovers. Even if teachers are opposed to minimalist fingering and feel guilty about omitting the fifth finger, students can always benefit from practicing fast, repetitive pentascales. There are hardly any better exercises for beginners and intermediates for developing thumb mobility and speed than fast, repetitive pentascales.

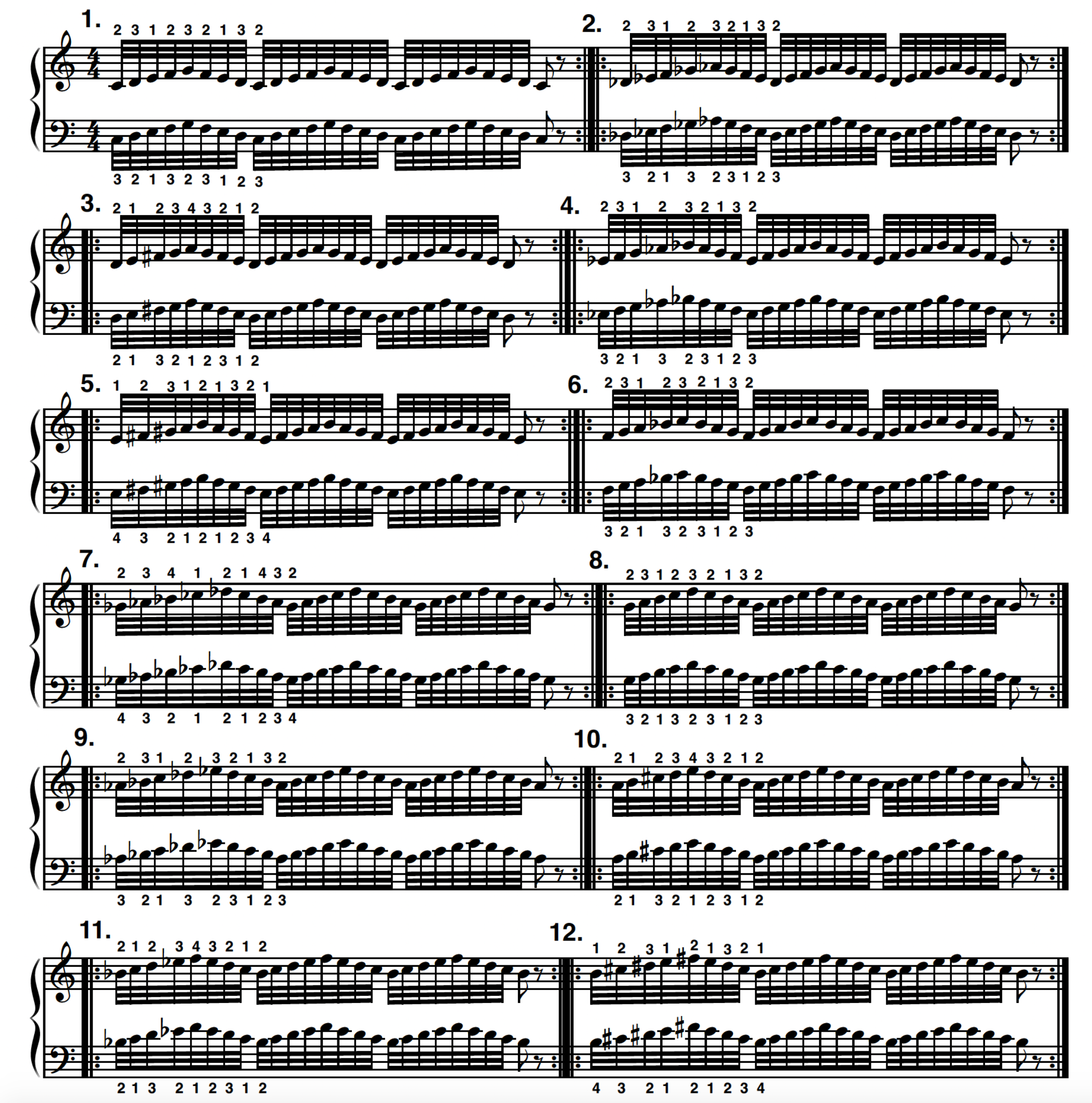

Below are all 12 major pentascales with suggested fingerings. Most of them have at least two or sometimes three other fingering possibilities; however, these particular fingerings have been chosen due to simplicity. Notice that most of the 12 suggested fingerings use only three fingers, 123, where the fourth finger is used only for necessity. Also, both thumbs always play at the same time, which further makes the fingering as easy as it can possibly be. Playing fast pentascales with just three or four fingers with fingerings like these (or with similar fingerings) creates an invigorating feeling, as if the thumbs are imbued with extra power. This exercise should be required for all beginners and intermediates. Start slow and progress up the tempo scale. Most importantly, focus on the evenness of touch. The greatest technical tip here is to keep the thumbs up at about a 20-30 degree angle instead of playing them totally flat on the sides. Strike the left thumb on the flesh near top right corner of the thumbnail and the right thumb on the flesh near the top left corner of the thumbnail. Avoid playing with a flat thumb where it strikes the key on the bone at the first joint. Playing with flat thumbs is one of beginners’ biggest mistakes. These are great, invigorating exercises and no fifth finger is required!