Book in Progress: Sight-Reading & Rhythm

(Updated: May 2022) This article summarizes Dr. Hall’s book-in-progress Sight-Reading & Rhythm. It is planned to be a big, spiral-bound book (about the size of Dr. Hall’s best-selling Sight-Reading & Harmony) packed with useful exercises and training for students and teachers. As the title suggests, the goal is to develop rhythm skills so that pianists’ sight-reading abilities improve, particularly in regards to rhythm and related topics. Sight-Reading & Rhythm is projected to be a big and thick spiral-bound book about the size of Sight-Reading & Harmony. It is projected to consist of six units, each leading to the next. For example, one must completely pass the skills in Unit 1 before moving on to unit 2, and so forth. One unique characteristic about Sight-Reading & Rhythm is that 90% of all the material is written with rhythmic notation whereby students tap, count numbers, or say syllables. Except for some traditionally notated scales in Unit 4, virtually all of the book consists exclusively of rhythmic notation.

When I wrote my popular book Sight-Reading & Harmony in 2016-2017, my main objective was to address what I believe to be two of the most pressing problems encountered by pianists today, namely, note and chord identification. I believe the next pressing problems are the related issues of rhythm and tempo. So, here I am a few years later writing a book addressing several important and foundational issues pertinent to rhythm and tempo. This book offers a systematic approach to rhythm, tempo, counting, and related topics. It is based on my experience of 50 years as a pianist and over 35 years teaching piano and music theory.

Pianists often confuse the two terms, rhythm and tempo, as these two terms are often used interchangeably when they really should not be. For simplicity and clarification, rhythm may be defined as “a repeated pattern of sound” while tempo may be defined as “the speed of a piece or passage of music.” In other words, rhythm is “qualitative” while tempo is “quantitative.” The two are inseparable and go together, yet the two are not the same. When one executes a rhythmic passage, one also must choose a tempo, whether this choice is conscious or not; however, one cannot execute a tempo without any rhythms. Here is an overview of the chapters and what they entail:

Unit 1: Counting Fundamentals – Before one learns formal musical notation, namely, note and rest values and time signatures, one needs to learn the fundamentals of counting. This is not as easy as it seems. To learn counting from the inside out, one needs to develop four skills, summarized below. The fourth skill, polyrhythms, should be skipped by beginners and only practiced after Unit 4 has been completed. More advanced students and teachers, however, are encouraged to practice the polyrhythm exercises in this unit either as preparation to or along with the polyrhythm exercises in Unit 4.

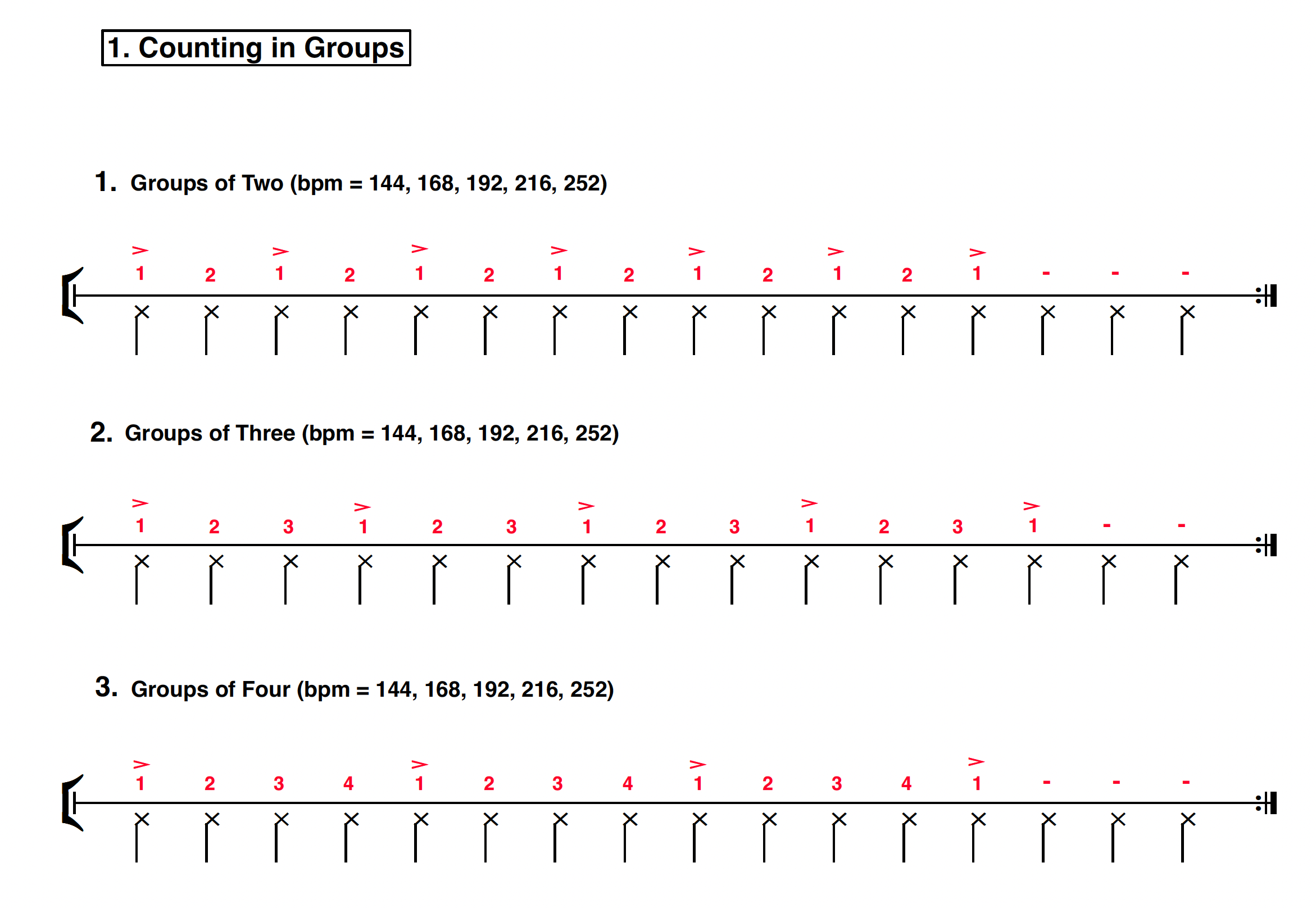

Counting in Groups – The first and most basic and primal of all rhythmic skills is counting in groups of one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, and eight using a metronome set on a fast beat. This skill requires one to say a syllable on each tick of the metronome. After these exercises are mastered, then the next skill can be practiced, which is consolidating fast beats.

Consolidating Fast Beats – This skill requires one to hear a fast tick on the metronome and be able to say a syllable for every two, three, four, five, six, seven, and eight ticks. After these exercises are mastered, then the next skill can be practiced, which is subdividing slow beats.

Subdividing Slow Beats – This skill requires one to hear a slow tick on the metronome and be able to subdivide this tick into two, three, four, five, six, seven, and eight equal parts using numbers and syllables. The skill of subdividing slow beats is more difficult than the previous skill of consolidating fast beats and is perhaps the most useful of all rhythmic skills. Most beginners struggle with subdividing slow beats, so this skill needs to be practiced carefully and with extra diligence.

Polyrhythms – As stated above, this skill should be skipped by beginners and only practiced after Unit 4 has been completed. This skill requires one to hear a certain number of ticks on the metronome and say a different number of evenly distributed counts or syllables for this duration of time. For example, for every four ticks on the metronome one counts to three equal parts. Then, for every three ticks of the metronome one counts to four equal parts. The polyrhythms covered here and in Unit 4 are: 3:2, 4:3, 5:3, 5:4. Polyrhythms are a neglected skill, and unfortunately, even many advanced pianists are deficient in the most basic polyrhythms, 3:2 and 4:3. Thus, to become a master of rhythm and tempo proficiency in polyrhythms is mandatory.

Unit 2: Note and Rest Values, Rhythmic Patterns – Learning counting fundamentals in Unit 1 requires little to no knowledge of formal musical notation. Instead, it is primarily an aural skill that builds a solid rhythmic foundation. In other words, counting fundamentals is “practice” more than “theory.” After one becomes proficient in counting, the units that follow are more theory than practice, the first of which is note and rest values. Traditionally, note and rest values are taught simultaneously with counting; however, this approach is backwards, since note and rest values will never be successfully executed until one first has a firm foundation in counting. Thus, counting comes first, then learning note and rest values logically follow. This book uses a unique and untraditional approach to learning note and rest values, in that formal symbols like quarter notes and quarter rests are presented and practiced with no reference to time signatures, which is covered in Unit 3. It becomes possible to cover note and rest values without reference to time signatures, and quite fun and easy to understand, when explained in context with the “Six Medieval Rhythmic Modes.” Medieval composers and theorists (in the 1200s, mainly in France) had a refreshingly simplistic way of explaining and categorizing rhythms in terms of “longs” and “shorts,” which makes up the foundation of this unit. Even young children should have little problem understanding the concept of “longs” and “shorts,” as this concept is no different than understanding basic arithmetic like “2” is two times longer than “1” or “3” is three times longer than “1”. This unit is taught using various techniques, which include counting with numbers and syllables (like in Unit 1), clapping and tapping, and using words and short word phrases as mnemonic devices.

Unit 3: Time Signatures – After first becoming proficient in counting fundamentals then progressing to note and rest values and rhythmic patterns, the learning of time signatures logically follows. Most methods teach time signatures simultaneously with note and rest values and counting, which demands far too much at once from the learner. One cannot possibly learn time signatures without first properly learning how to count, using a metronome, and recognizing all the various note and rest values. On the other hand, if one is already proficient in counting with a metronome and can already apply this skill to note and rest values and rhythmic patterns, then learning time signatures becomes much less difficult. This book uses a fun and practical method of teaching time signatures. Unit 3 organizes time signatures into simple and compound meters whereby all the common time signatures are introduced using rhythmic phrases from time tested musical works. All these rhythmic phrases are the opening few bars from standard piano and keyboard works by the great composers as well as some traditional folk songs and church hymns. Each musical example functions as an exercise supplied with a suggested metronome speed and step-by-step instructions on how to count, tap, and interpret the rhythmic phrase. Each example is referenced with the composer, work, and opus number so that teachers and students may look up the work. All examples in each time signature category are organized in a progressive fashion from easiest to most difficult, which makes it easy for teachers and students to work their way through each time signature. If one works through these examples in a systematic and progressive fashion, understanding and interpreting time signatures in other musical works at the piano will become easy and enjoyable.

Unit 4: Polyrhythms – Superimposing one rhythmic group over another, known as polyrhythm, creates one of the most perplexing problems encountered by pianists. From the relatively simple 2:3 polyrhythms to the more complex 3:4 and 3:5 polyrhythms, this chapter explains the mathematics behind the most encountered polyrhythms and offers solutions and useful exercises on practicing and mastering them. This chapter also includes a list of standard solo piano works that contain polyrhythms, which students and teachers may use for reference and study.

Unit 5: Tempo & Tempo Relationships – One of the biggest problems students have with sight-reading is establishing a good, solid tempo for the music with they are reading or learning. This unit offers helpful solutions for this problem with the use of a practical tempo matrix that consists of all the metronome speeds one will ever need in any music. By learning the differences between slower, moderate, and faster metronomic speeds (mostly from the counting exercises learned in Unit 1), tempo will become a much less elusive concept.

Unit 6: 6-Tier Progressive System of Rhythm – Part 4 of Sight-Reading & Harmony consists of a highly effective 5-tier progressive system that moved down each page with Grades 1-2 at the top and Grades 9-10 at the bottom. A similar plan is projected for this unit in Sight-Reading & Rhythm where the top line will be a relatively simple phrase in rhythmic notation, which will progressively increase in speed and complexity as it moves down the page.

Sincerely, Cory Hall (D.M.A.) — May 2022