New Edition of Bach’s “Goldberg Variations”

(Updated: May 2022) This article summarizes BachScholar’s new groundbreaking edition of Bach’s “Goldberg Variations,” which explains Bach’s symmetrical tempo plan indicated by the use of fermatas. This attractive Urtext of Bach’s popular variation cycle is not only extremely user-friendly and extra-legible, but in addition, presents thought-provoking performance practice research that explains Bach’s never-before-revealed plan of tempo relationships between variations. This discovery is highly significant with regards to the tempi chosen for the variations in a complete performance. Almost all editions incorrectly reproduce Bach’s fermata indications, which makes it impossible for serious artists and scholars to know the kinds of tempi and tempo relationships Bach intended. BachScholar’s beautiful new Urtext is the only edition that correctly honors and explains Bach’s true intentions with regards to tempo relationships between variations.

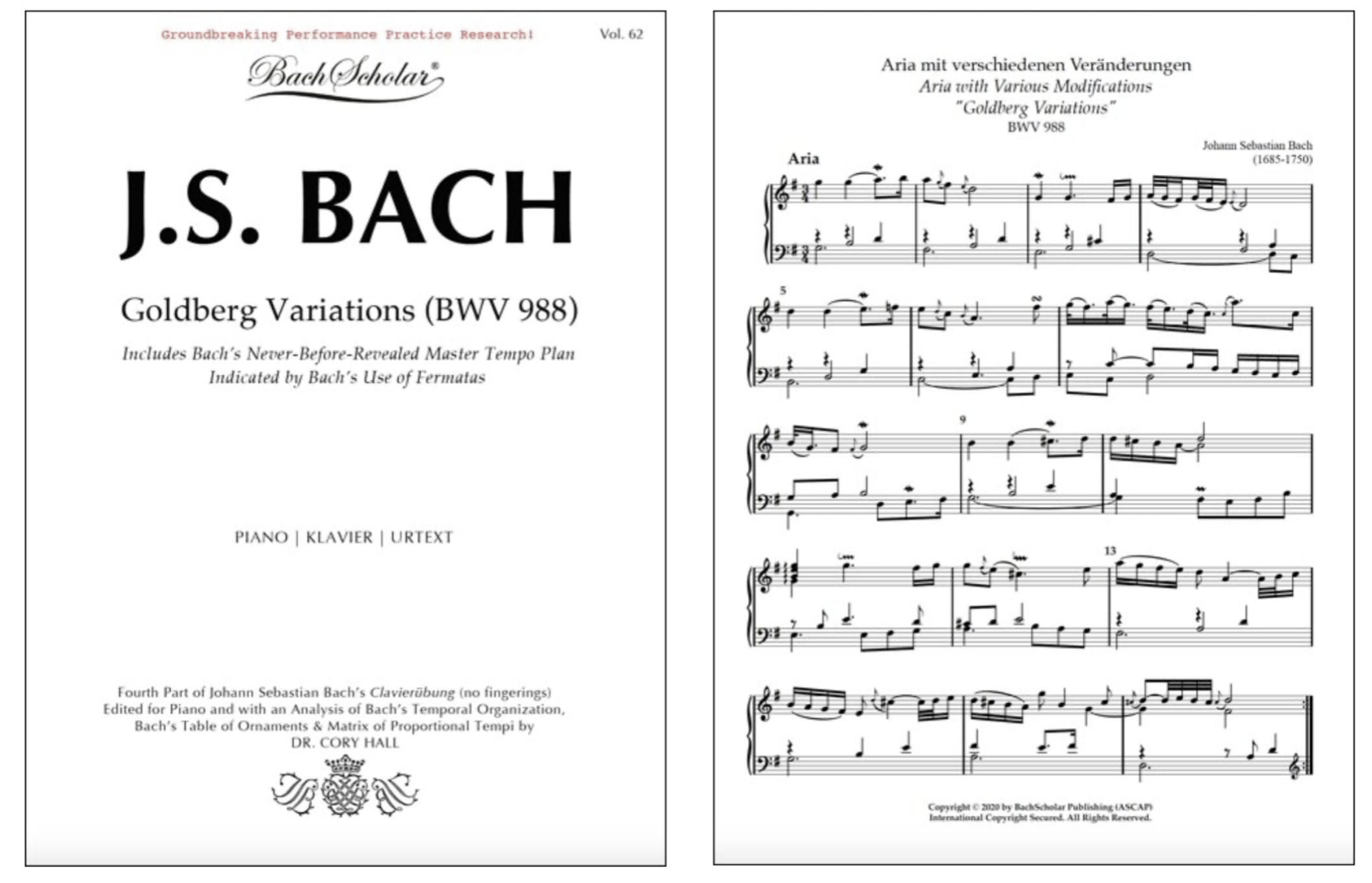

The cover and first page of BachScholar’s edition of Bach’s Goldberg Variations.

This edition of the fourth part of Johann Sebastian Bach’s (1685-1750) Clavierübung, popularly referred to as the “Goldberg Variations,” presents the composer’s work in a clean, performance-oriented Urtext edition with no fingerings. This edition precedes and prepares for a forthcoming volume by BachScholar Publishing, The Ultimate Guide to Bach’s Goldberg Variations for Amateurs & Professionals. The latter volume includes the present Urtext with the addition of copious fingerings, essays and explanations pertinent to the practice and performance of the variations, simplified versions of some of the variations for less advanced players, four-hand arrangements of the canons for students and teachers, a detailed analysis of Bach’s temporal organization of the complete opus for advanced pianists and professionals, metronome speeds for all the variations, and more.

The main editions consulted for the present edition, listed in chronological order of publication, are: First Edition (Bach’s Handexemplar, 1741), Peters (ed. Kurt Soldan, 1937), Bärenreiter (ed. Christoff Wolff, 1977), Henle (ed. Rudolf Steglich, 2009). In addition to these publications, the discussion of Bach’s temporal organization below and on the next page as well as much of The Ultimate Guide volume has been inspired by and based upon my own article “Bach’s Goldberg Variations Demystified” (American Music Teacher, April/May 2005). Moreover, this edition would not have been possible without my over 25 years’ experience playing and teaching the work.

In his personal copy of the first edition from 1741, known as the “Handexemplar,” Bach made several minor additions and corrections. Since Bach’s Handexemplar was discovered in 1974, all editions published before this date obviously did not have these changes. Other than the “al tempo di Giga” indication added to Variation 7, which indicates a fast gigue-like tempo rather than an otherwise slow pastorale-type tempo (as it had often been played up to this time), the corrections that have the most significance for performance are Bach’s additions of appoggiaturas in Variation 26 (i.e., the small notes that look like grace notes).

Bach’s addition of an appoggiatura in the 3/4 part of Var. 26.

To avoid any ambiguities and questions as to how these appoggiaturas are to be played and to assist students and teachers, I have notated them literally with normal-sized notes and aligned them vertically in their proper positions. In addition, I have also vertically aligned the final 8th notes of the 3/4 bars and the 16th notes leading into the second beat of the 3/4 bars as Bach did in the first edition. Most editions align the former with the fourth sextuplet note; however, in all but the first four bars Bach aligned these 8th notes with the fifth sextuplet note. The reason for this is the vertical harmony that results with the 8th note on the fifth sextuplet note is always more complete and theoretically sound than on the fourth sextuplet note.

Bach’s alignment of notes in bars 8-9 of Var. 26.

Bach’s addition of so many appoggiaturas to Variation 26 strongly suggests that he conceived this variation in a much slower tempo than traditionally played by modern performers, since these expressive ornaments necessitate a slower-style sarabande (not unlike the Aria, which is also in the style of a sarabande). The rolling sextuplets in the 18/16 part simply provide a moderate-speed accompaniment to this sarabande, not unlike the identical triplet 16th notes in the Sarabande from Partita No. 3 (BWV 827). Seen in this light, the extremely fast 19th-century etude-like tempo for Variation 26 we are all used to hearing must seriously be questioned.

The most significant detail that allows us to reconstruct Bach’s intentions regarding the variations’ tempi and tempo relationships between variations in a complete performance is the presence or absence of fermatas. Close study of first edition, Bach’s Handexemplar (which is publicly viewable on IMSLP), shows that Bach indicated a fermata only after some, but not all, variations. Moreover, Bach indicated an artistic swirly-style flourish after most variations with no fermata termination. Bach’s choice of separating variations by either a fermata or artistic flourish is highly significant and is obviously no mistake. Most editors assume the absence of some fermatas to be an oversight by Bach, and thus, add fermatas where Bach did not indicate them. To my knowledge, the only addition that reproduces Bach’s fermatas correctly (aside from the present edition) is the Peters edition from 1937 edited by Kurt Soldan. All other editors add fermatas where they do not belong.

Bach’s use of fermatas is addressed in detail in The Ultimate Guide volume mentioned above; however, just to summarize here, Bach apparently had an ingenious “master plan” organized according to an impressively symmetrical arrangement of variation pairs and groups unified by a diverse plethora of direct tempo relationships. When the complete cycle is mapped out, it becomes evident that when there is no fermata between variations, and thus, usually his personalized artistic flourish instead, Bach intended a segue and direct tempo relationship between the variations. Otherwise, there would have been no reason for Bach to have omitted fermatas in such a systematic fashion that happen to create almost perfect symmetry with variation pairs and groups. Since the present edition is intended as a clean and neutral Urtext, tempo relationships rather than actual metronome speeds are provided. Actual metronome speeds are given in The Ultimate Guide volume. The next page provides a summary of Bach’s fascinating and ingenious plan.

Variation pair 16-17 represents the mid-point of the Goldberg Variations. Bach indicated no fermata after Var. 16, which implies a segue and direct tempo relationship with Var. 17. Moving outwards in either direction from the Var. 16-17 mid-point lie three variations each with fermata terminations, 13-14-15 on the left and 18-19-20 on the right. These three single variations on either side of the mid-point may or may not share direct tempo relationships, which is investigated in greater detail in The Ultimate Guide volume. The fermatas here most likely indicate a greater pause and no segue between each variation in a complete performance rather than necessarily no tempo relationship.

Moving outwards in either direction from the three single-variation points lie two variation pairs on either side, 11-12 and 9-10 on the left and 21-22 and 23-24 on the right. These four pairs share four distinctly different tempo relationships, suggesting that Bach intended to diversify the tempo relationships as much as possible. So far up to these points, Bach’s plan is perfectly symmetrical: 2-2-3-2-3-2-2.

Moving outwards in either direction from this point lie a three-variation group on the left, 6-7-8, and a variation pair on the right, 25-26. Both units display “slow-fast” progressions, in that the relaxed tempo of Var. 6 speeds up two times to the “al tempo di Giga” of Var. 7, which is continued in Var. 8. Similarly, the “adagio” of Var. 25 (this indication was added by Bach in his Handexemplar), speeds up two times to the livelier but still relatively slow sarabande tempo of Var. 26. Bach’s addition of expressive appoggiaturas in his Handexemplar suggests Var. 26 is, at the fastest, only moderate in tempo and only two times faster than Var. 25 in terms of quarter-note speed, rather than the extremely fast, prestissimo 19th-century etude tempo taken by virtually all modern performers.

Moving outwards in either direction from this point lie a four-variation group on the left, 2-3-4-5, and a variation pair on the right, 27-28. In contrast with the “slow-fast” units before this which consist of “1:2” tempo progressions, these two units display equal tempo relationships where the 8th and 16th notes simply remain equal throughout. Vars. 2-3-4-5 are unified by a constant 8th-note speed, which creates simple “metric modulations”: between Vars. 2-3 (8th notes in groups of twos that modulate into groups of threes), and between Vars. 4-5 (8th notes in groups of threes that modulate into groups of twos). In Vars. 27-28, the illusion of a tempo twice as fast in Var. 28 is created by Bach’s addition of 32nd notes; however, the speed of the 8th and 16th notes in this pair remains unchanged.

Moving outwards in either direction from this point lies two units on the left, Aria and Var. 1, and three units on the right, Vars. 29-30 and the Aria da capo. The Aria and Var. 1 as well as Vars. 29-30 and the Aria da capo may or may not share direct tempo relationships, which are investigated in greater detail in The Ultimate Guide volume. Most performers and listeners take the final Aria da capo for granted, not realizing that Bach was not obligated to end the cycle with the exact same theme as stated in the beginning. In fact, this is perhaps the only time in musical history up to this point in which a theme and variations cycle ended with an exact restatement of the original theme. (John Bull’s Walsingham Variations from ca. 1600 also consists of 30 variations, however, the final variation is reminiscent of but still significantly different than the opening theme.) Bach’s use of the same piece at the beginning and end (i.e., the “Alpha and Omega”) unifies the outer pillars with equal tempi, which consummates and symbolizes the near-perfect symmetrical temporal organization he achieved for the inner 30 variations.

To summarize, Bach’s placement of fermatas contributes to an impressively symmetrical plan consisting of 30 variations with the Aria standing as pillars at the beginning and end. Bach created seven variation pairs (9-10, 11-12, 16-17, 21-22, 23-24, 25-26, 27-28), one three-variation group (6-7-8), and one four-variation group (2-3-4-5). Virtually every possible direct tempo relationship occurs among these nine units. In addition, Bach created nine variations that each have fermata terminations (1, 13-14-15, 18-19-20, 29, 30), which indicate no segue and possibly no direct tempo relationships, which require further investigation.

Sincerely, Cory Hall (D.M.A.) — December, 2019